On August 27, NASA’s Juno mission completed the first orbital flyby of Jupiter. Traveling at a speed of 130,000 mph, the spacecraft passed about 2,600 miles above the gas giant’s swirling clouds. Though the space probe will be conducting 35 additional flybys before the mission ends on February 2018, this was its closest approach and hence, the most important for data collection. Juno did not disappoint.

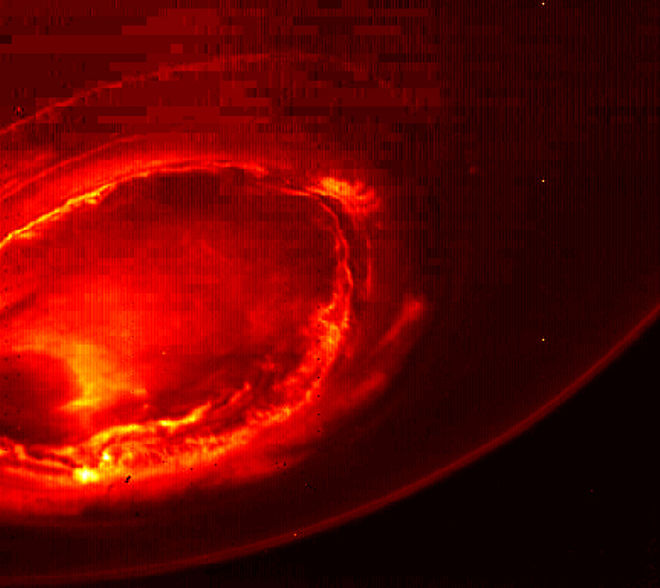

The space probe not only captured stunning images of Jupiter’s North and South Poles, but also recorded the radio emissions from the planet’s auroras. Similar to Earth’s Northern and Southern lights, the auroras are a result of high-energy particles in the atmosphere colliding with atoms of gas near the magnetic poles. Jupiter’s auroras, however, are massive and more spectacular than ours.

The radio emissions, recorded above Jupiter’s North Pole by a University of Iowa (UI) instrument called Waves, are not audible. They, therefore, had to be converted to sound files and “downshifted,” to a range perceptible to the human ear. Once done, UI senior engineering associate Don Kirchner, compressed the 13-hours of tape to just 40 seconds of most dramatic sounds. The result? A spooky audio track to get even the most jaded of us into the spirit of Halloween! Besides being fun to hear, the data collected by Juno also paves the way for an in-depth analysis of the emissions which were first detected in the 1950’s.

According to Bill Kurth, research scientist at the UI and co-investigator for Waves, "Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras that encircle Jupiter's north pole. These emissions are the strongest in the solar system. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons that are generating them come from." The researcher says he decided to share the audio clip with the world because, “We figure if we like to listen to them, others will too!”

Happy Halloween!

Resources: Sciencedaily.com, now.uiowa.edu